The responses of the Portuguese higher education to the COVID-19 Pandemic: the case of Lusófona University

Manuel José Damásio

- Head of the Film and Media Arts Department

- mjdamasio@ulusofona.pt

Abstract

This paper presents the case study of the response of Lusófona University (Lisbon) to the COVID-19 pandemic. The paper characterizes that response as a multidimensional process that we classify as original precisely because of the way in which it combined different dimensions in order to guarantee the success of the adoption process of an innovation in higher education as a response to the crisis situation triggered by the pandemic. Four dimensions are described and analysed: institutional; technological, teaching/learning and brand management. The main finding illustrated by the case study is the relevance that the use of an integrated brand management process and the involvement of all stakeholders had in the successful response to the crisis. Starting from a framework typical of the crisis management theory, we will see how the originality of the case lies in how the institution was able to combine all these dimensions in an integrated manner, thus guaranteeing what we identify as a mosaic response to the crisis. The case study follows a chronological structure to describe the major events that occurred throughout the crisis, describing how, at each moment, and for each of the dimensions under analysis, the institution was defining its policies and actions in order to the crisis mitigation and possible resolution.

Keywords: stakeholders; branding; educational innovation; remote teaching

1. Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic was a highly disruptive event in our social and economic activity and the full consequences of this event are still difficult to predict. Among the many sectors deeply affected by the crisis associated with the spread of the coronavirus, the educational sector, and the higher education sector in particular, were deeply affected as a direct consequence of the confinement that many European countries, including Portugal, decided to impose in March 2020 as part of their strategies to fight the virus. This paper presents the case study of the specific response of a Portuguese higher education institution, Lusófona University in Lisbon. The analysis of this process is carried out with a focus on four dimensions that are considered pivotal to understand the options taken: institutional; technological, teaching/learning and brand management.

The period of temporary suspension of all teaching activities, decided by the institution at the beginning of March 2020 as a preventive measure in view of the conditions caused by the Coronavirus, served for the rapid definition and implementation of a strategy that involved the adaptation of the teaching-learning processes and the management model to support this change. Particular circumstances promote increased challenges, which is why the Lusófona University management bodies decided to promote, in advance, all the necessary measures for the pursuit of their educational project, considering at all times, all the needs and concerns of those who make up their academic community, that is, all its internal stakeholders. The process that we describe in this paper, following a chronological methodology that frames the organization's decisions and actions at every moment, corresponds to a typical crisis management process.

The institutional dimension concerns all components of the activity of a higher education institution that converge in order to fulfil its mission. We, therefore, integrate in this dimension all internal and external stakeholders that actively participate in the institution’s life. Our definition of a stakeholder refers to the definition by UNESCO which, at its 1998 Paris conference, defined as stakeholders of a higher education institution the teachers, the students, the parents, the public institutions, the private institutions and society at large, as entities that contribute to the pursuit of the institution's mission and its governance (UNESCO, 1998). Our analysis of the institution's response to the crisis will by particularly focus on how it sought the engagement of internal stakeholders in order to guarantee the success of the process.

The technological dimension relates to the entire application and structural environment in terms of information systems, which the institution used to be able to leverage its effort to respond to the challenges raised by the crisis. A central point of our argument is that all the components of this dimension were already partially or fully implemented in the institution and the only thing produced by the crisis was an imperative need to diffuse its use. The obvious consequence of this massification was a much greater pressure on the institution's structures, which turned out to be the major variable of the institution's response in technological terms, more than the adoption and diffusion of this or that specific technology and innovation.

The teaching and learning processes dimension concerns the whole pedagogical and training component that corresponds to the institution's activity and, which in this case, is embodied in the offer of teaching and research activities. When the crisis began, the institution offered different study cycles conferring degrees organized according to the principles of the European higher education space, in addition to different non-degree training courses corresponding to vocational development or lifelong training programs. At the beginning of the crisis, the institution did not offer any distance learning program or any other type of educational offer supported on digital platforms. One of the consequences of the crisis was precisely the implementation of a dedicated program of MOOCs supported on a customized version of the Open edX platform called Lusófona X.

Finally, the brand management dimension concerns all the institution's identity management processes, including promotional processes integrated in the communication aspect of the company's marketing policy, and also all the management components of the institution's value proposal. One of the central aspects of the institution's response to the pandemic was the decision to create a unique brand, “Click”, which would aggregate all the different dimensions of innovation. The creation of this unique brand not only facilitated the whole communication process, but also added value to innovation, making something that was not a “novelty” from the technological point of view take on this characteristic as an integrated proposal for an innovation in the communication process in the institution and provision of teaching and learning services.

Thus, our study presents a multidimensional analysis of the adoption of an innovation - teaching mediated by synchronous and asynchronous digital technologies, in a Portuguese higher education institution, and argues that the institution's response to the COVID-19 pandemic was characterized by the adoption of an integrated strategy that highlighted the organizational and management aspects in order to ensure the control over the process and the widespread adoption of the proposed innovation. The predisposition for the change which the data presented show was obviously a relevant factor in the success of the institutional response, but, as we will see later, it was the adoption of a model focused on the engagement of all stakeholders at all stages of the process that guaranteed its effectiveness and success (Damanpour & Schneider, 2006).

2. Theoretical framework - how to address a crisis?

The definition of what is a crisis in an organizational context was established by Charles Hermann in 1963 as an event that threatens the fundamental values of an organization, forcing it to take decisions in a short period of time (Hermann, 1963). This classic definition has been complemented over the decades by different studies that have not ceased to focus on the definition of a crisis as something extraordinary and unpredictable. Something that takes on large proportions and that can have significant impacts for an organization and which may ultimately lead to its extinction (Barton, 1993; Bland, 1998; Heath & Palenchar, 2009). A crisis interrupts the normal course of activities of an organization, challenging all those involved in it to try to react to it. Fearn-Banks (2011) defends five stages in a crisis: detection, prevention/preparation, containment, recovery and learning. An organization in crisis must first develop an action plan to react to the situation, but it will only be successful if it can prove to its public that the negative situation is overcome.

The COVID-19 pandemic falls under the classic definition of a crisis, whatever the perspective from which one looks at this event. The pandemic was a largely unpredictable event and posed enormous challenges for all organizations that were affected by its effects. As in any crisis, its origins can be very different. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, the most curious aspect of the entire process is that the crisis in question resulted not exactly from the main effect of the pandemic - the infection - but from the measures adopted to stop the pandemic and, in particular, the confinement decision of most of the population, thus preventing their access to different activities, namely teaching. That is why it is not easy to classify this crisis in some of the best known classic typologies in the literature, such as the typologies of Myers and Holusha (1986), Barton (1993) or Fearn-Banks (1996). All of these typologies are defined according to hypothetical scenarios (e.g. a natural disaster) that can trigger an organizational crisis.

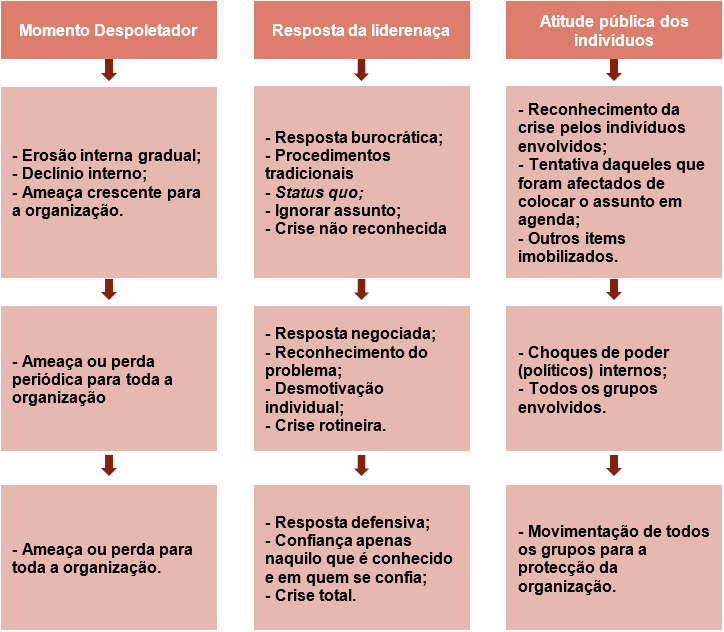

In the particular case of this crisis, and in order to understand the response to it, we must look at other classification systems. According to Booth (1993), the classification of the crisis must be based on the principle that the impacts of the crisis on the organization vary according to the predictability of the events that trigger it, thus leading to different responses. Figure 1 illustrates this classification system and explains how the different events that integrate a crisis vary along an axis of regularity of the cause, that is, the predictability or not of the event. Depending on the types of crises, the way in which changes are perceived by the individuals who are involved in them also varies, as well as the effects that the crisis might have on the way they act.

According to this typology, the COVID-19 pandemic can be classified as a “total crisis” that would call for a defensive response from the organization's leadership and the action of all the groups involved - the internal stakeholders - to respond to the crisis. One of the fundamental ingredients of this type of response is the leadership's confidence in what is known and in those they trust. In the particular case of the COVID-19 pandemic, this was precisely the response and the defence involved implementing the innovation in question in a short period of time - the use of digital technology to continue supporting the teaching activities, ensuring in the first place the engagement of those who were the most trusted - teachers and middle managers.

It is the defensive nature of the HEI's response, which is common to most entities which have had to react to the pandemic, that justifies the adoption of an offensive solution that could involve an attempt to fully turn the teaching and learning processes into distance learning models. Instead, what was done was to opt for a defensive response in which the teaching activities continued in the same synchronous models but switched to a remote system using technology. This remote education model does not correspond to an effective distance learning model (Damásio, 2007), but rather to an intermediate stage, which, given the unpredictability and violence of the crisis, the HEI was able to implement in a short period of time. Another relevant aspect was the use of existing and implemented technologies, what was trusted, as a way of limiting the degree of innovation and risk.

In addition to the central role played by the leadership in aggregating the dimensions under study in the crisis response model, another central aspect of this response was the engagement of stakeholders in the crisis management (Coombs, 1995), namely in what was its essence, the service interruption. The unpredictability of the crisis (Ferrer, 2000) configured it as an acute crisis process that demanded an efficient and planned response from the organization. The organization was aware of this and made one of the most important decisions in this entire process, which was to create a “buffer” period of ten days that allowed it to prepare itself to react efficiently to the crisis.

If we look at the typology of the Institute for Crisis Management (2009), we can see that the type of crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic does not fit into the most common types of crisis in the last decade that are mostly associated with natural phenomena or events caused by human action such as terrorism. The highly unpredictable nature of the crisis made it very difficult for any educational organization to anticipate it, thus preparing its response to the crisis according to the precepts defined in the literature (Laugé et al, 2009). That is why, unlike other cases, this crisis did not have a preliminary prevention phase. The major consequence of this fact was that the response of the institutions was made in most cases, on the one hand, with means that they already had at their disposal (e.g. existing distance learning platforms) and, on the other, using methodologies that responded exclusively to the major risk for the continuation of the organizations’ activity, that is, the response was focused on ensuring that it was possible to continue the teaching activities.

Since crisis management is a process dedicated to strategically planning the removal of risk and uncertainties from negative occurrences of a crisis, in order to put the organization back in control of its own destiny (Fearn-Banks, 2011), the type of response developed by the Lusófona University to this crisis is part of a crisis management process. In this particular case and as we have already mentioned, the crisis did not have any pre-crisis moment (Coombs, 2007), and, therefore, our case study is focused only on the crisis moment itself, especially because it is still too early to assess the post-crisis moment.

Laugé et al (2009) states that in the face of a crisis scenario, the organization must respond quickly, with persistence and consistency, and the establishment of a crisis plan is crucial. In the particular case under analysis, the crisis plan involved the implementation in a short period of time of an integrated solution called “Click”, which allowed guaranteeing that the crisis caused by the interruption of the service could be mitigated. But that alone is not enough!

In the approach adopted, we identified four key moments in the response to the crisis:

- a) Identification and categorization of the phenomenon that triggered the crisis with the objective of assessing the impact of the crisis and defining the nature of the relationship with the stakeholders that has to be implemented in order to overcome the crisis. In the case of Lusófona University, after the closure of classroom activities, the suspension of teaching activities was identified as a central phenomenon and, therefore, the entire effort to solve the crisis was oriented towards the implementation of a response that would guarantee that these activities could be resumed. In parallel, it was defined that in order for this to be successfully conducted, it was crucial to establish a constant relationship with the internal stakeholders - students, teachers and employees - in order to guarantee their engagement and adherence to the solution. It was established that this relationship would comprise four elements: training, technical support, pedagogical support and psychological support;

- b) Identification and characterization of the stakeholders in order to understand the relationship they have with the proposed innovation and how they can influence the crisis process. This was done through multiple surveys aimed at assessing the degree of readiness for the assessment of the proposed innovation;

- c) Selection and preparation of the crisis response strategy and its tactical aspects, which was nothing more than selecting and preparing the strategy indicated for responding to the crisis, using the existing technological tools;

- d) Activation of the response system, which integrated the multiple aspects of the institutional, technological, teaching/learning and brand management dimensions.

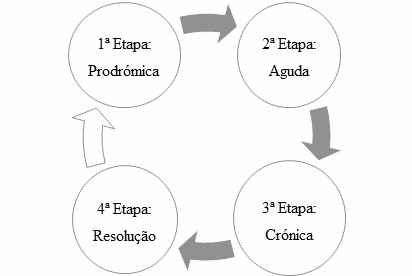

The crisis cycle was very similar to the models studied in the literature (Coombs and Holladay, 2010), with the crisis going through four stages as shown in Figure 2. The first is the so-called prodromal, which corresponds to the moment when the first warning signs for a possible crisis in the organization show, followed by the acute stage, which is when the crisis occurs, then the chronic stage, which corresponds to a stage where the crisis “normalizes” and conditions are created for a recovery period. Finally, there is the resolution stage, which is when the organization returns to a normal routine.

All crises have a cycle and this crisis was no different. The presentation of our case study will therefore be organized according to a timeline that follows these different stages. Before moving on to the description of these different moments of the crisis and the response designed, let us look more closely at the importance that the stakeholder involvement had for the management of this crisis and globally has for the management of any higher education institution, as well as for the characterization of each of the dimensions integrated in the response of the Lusófona University to the crisis.

3. The institutional dimension - the stakeholders’ role

Freeman (1984: 29) defines the stakeholders in the life of an organization as "any group or individual that may affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization's objectives". The author shows in this definition of stakeholders his adherence to other definitions of the concept that we find in the literature, such as Bryson (2005: 22) who speaks of “people, groups or organizations that must be taken into account”.

Therefore, stakeholders are all players who can gain or lose from an organization's activities. The stakeholders can be divided into two groups: internal and external stakeholders. As the terms suggest, the internal stakeholders come from within the organization and the external stakeholders are those who are outside the organization, but have a personal interest in it. Thus, for example, teachers considered individually are themselves the main stakeholders in their academia’s life, since their interests are closely dependent on the performance of their institutions. However, as higher education institutions have to account for their activities to a significant number of people and to society at large, external stakeholders have gained supremacy in the academia in recent decades, as seen in our country, for example, through the relevance given in the RJIES - Regime Jurídico das Instituições de Ensino Superior (Legal Regime of Higher Education Institutions) to the participation of representatives of civil society in the institutions governance. Generally, the group of external stakeholders includes regulators, legislators, funders, but also the civil society in a more general sense. The separation between internal and external stakeholders is not always clear, particularly as the involvement of different players in the activity of institutions increases. The extension of the Universities' mission to all vertices of the so-called “knowledge triangle” further contributes to this blurred borders.

When formulating a stakeholder theory in higher education, one of the main problems we are facing is precisely that of defining the role of teachers and researchers: we must consider these individuals as universities’ internal stakeholders, or rather as a crucial facet of the relationship between the university and other institutions, thus looking at the professor, not as an internal stakeholder interested in the institution's destinies, but rather as a fundamental part in the perception of the institution's value proposal, and should it therefore be seen as an external stakeholder? Benneworth and Jongbloed (2009) suggest that the distinction between internal and external stakeholders is less relevant when compared to the capacity that the stakeholder has, regardless of their position, to influence the organizational decision-making process.

In crisis management stage b), one of the institution's findings was the imperative need to engage the teachers in the whole process, ensuring that they not only adopted the innovation, that is, they started teaching their classes using digital technologies, but were also engaged in the crisis management itself. That is why we consider that an essential part of the Lusófona University's response to the crisis was to consider its teachers as internal stakeholders who had to be involved to the fullest in the entire process of responding to the crisis and in its management.

To make this possible, we had to focus our attention on the types of value that are produced by universities while trying to understand whether these are homogeneous and the type of valuation they are based on. When talking about a commercial company, this is a relatively simple question, because that value is defined in financial terms, but, when we are talking about a university and its stakeholders, this question becomes much more complex. For universities, this value refers mainly to the development of activities that will generate results that will guarantee the institution's sustainability in the long term. This can be defined in economic terms (e.g. the revenue generated by the intellectual property produced by the teaching staff), in terms of brand (that is, the degree of public recognition of the university's brand as measured by its degree of attractiveness to foreign students) or in political terms (that is, the level of services it provides to society measured according to the volume of local financing obtained). For the teachers, the question is completely different. Although individual objectives are sometimes aligned with institutional ones, in many other cases, academics define their notion of value by following information resulting from many-to-many relationships. This means that their notion of value is essentially oriented towards the recognition of peers. That is why if we consider academics as a specific group of stakeholders, their way of relating to the institution will vary according to the value expectations in question. If, for example, they are not equivalent, we will have a conflicting relationship. In the case under analysis, what we have is a situation in which the academics and the institution depend on each other and that is precisely why they were able to develop forms of cooperation in order to align their respective value expectations (Chapleo & Simms, 2010) and guarantee the engagement of all parties.

The previous propositions are aligned with a central aspect of the stakeholder theory, which is the principle that the value that the stakeholders obtain from participating in the organization may not be captured exclusively in terms of economic measures. While economic returns are often critical to an organization's key stakeholders, most stakeholders also want other things (Bosse, Phillips & Harrison, 2009). In this sense, stakeholders are both beneficiaries and bearers of risks for any organization. In the management of the crisis, Lusófona University guaranteed right from the beginning that the teachers understood that their engagement was essential to overcome the crisis and that the process would require an increased effort from them. In this sense, different actions were developed in order to ensure the engagement, through clear and permanent communication of action and decision making lines; and readiness for the adoption of the innovation through permanent training and technical support.

The stakeholder theory claims that the relationships between the parties can be characterized by three modes of interaction, which vary according to their objectives: scrutiny, dependence and conflict. These three modes are structured according to the core of what defines the relationship between an organization and its stakeholders - the creation of value - and the existing context that can hinder or facilitate the relationships focused on achieving this objective. The interaction modes that we have just listed can take on different configurations: actions that intend to capture the needs and expectations of value of the stakeholders; the cooperative creation of value to make full use of the resources available by the stakeholders; the satisfaction and fulfilment of the stakeholders' value needs to improve the stakeholders’ recognition and engagement in the life of the higher education institution. In its response to the crisis, Lusófona University tried to guarantee the engagement of teachers throughout all these configurations, creating an interaction based on a cooperative dependency and avoiding both scrutiny and conflict. In the case of the other two large groups of internal stakeholders - students and employees - the same exact approach was adopted, based on permanent communication, engagement in decision making, training and technical support. In the case of students, a psychological support axis was also added to the configurations of the relationship between the institution and the stakeholders.

The interaction modes between the stakeholders vary according to those relationships’ positive or negative outcome. The positive or negative outcome of those relationships is defined by the degree of subjective satisfaction with the process felt by each group of stakeholders. Aware of this aspect, another important part of the institutional dimension of the response to the crises focused on the permanent assessment of the degree of satisfaction of the stakeholders with the process.

In this part of our text, we saw how the institutional dimension of the University's response was structured through the identification of the stakeholders essential for the resolution of the crisis, defining a way of interacting with these parties based on different configurations that would guarantee their engagement in the value proposition. Our description underlined the importance that the institutional dimension had in the process by carrying out, based on the principles of the stakeholder theory, the identification of the variables that positioned the different stakeholders with regard to the crisis response model, followed by a network of relationships between these parties, teachers, students and employees, based on permanent communication, decision-making sharing, training and support, which guaranteed their engagement in the process and their satisfaction with it.

4. Technological Dimension and Digital Capacity Building

Among the many challenges that the COVID-19 pandemic entailed, the demands it brought in terms of the institutions' technological capacity was unquestionably one of the most relevant aspects. The particular demands that this new scenario brought to all organizations put great pressure on their installed capacity in terms of communication and information processing digital technologies.

From the moment that it was decided that the response to the crisis would be based on the technological component, on the provision of a distance learning solution that would allow to remotely continue the teaching activities previously designed to take place in face-to-face sessions, it became clear that the degree of capacity building in this dimension would be crucial to the success of the crisis response.

We know that the degree of adequacy and modernization of the technological infrastructure directly contributes to the capacity of institutions to ensure efficiency in the response to transformational processes, through the natural evolution and implementation of process innovations or through the imperative promoted by disruptive situations, such as this is the case of the pandemic crisis we are living. For the transformational process, variables associated with the institutional strategy and permanent engagement of its stakeholders, the physical infrastructure and the digital training of the academic community agents, teachers, students, and staff must be taken into account.

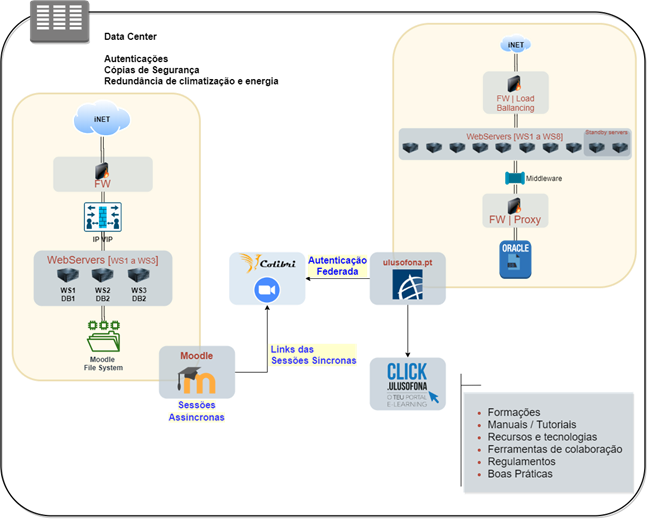

Since its foundation, Lusófona University has strategically invested in technology as a differentiating factor for the services it provides and, therefore, the pre-existing conditions, such as a laboratory park with more than eight hundred pieces of equipment, its own data centre, encryption procedures, centralized authentication, backup copies, an autonomous IT team, both in the systems component and in the development component, a consolidated b-learning solution, various application solutions (Microsoft Office365, federated services such as Coliri, Educast, among others), email accounts and associated cloud services for the entire academic community, or even iOS and Android applications for mobile devices for teachers and students, have become crucial.

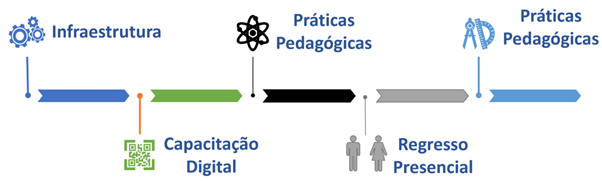

After the decision to suspend face-to-face activity, it was necessary to define the strategy to be adopted to face the constraints of the new reality, which is why the scheme in Figure 3 represents the main stages of the approach and adaptation process to a new reality.

i) Infrastructure

In the infrastructure variable, physical and logical aspects were taken into account. As for the physical aspect, and once the robustness of the information systems was guaranteed, in terms of load, integrity and systems and data security, it was necessary to make sure that the academic community agents had the technological conditions for the correct implementation of an distance learning system. In this sense, surveys to all students and teachers were promoted right at the beginning of the process in order to identify limitations for which the required measures were taken, involving the loan of equipment and the provision of dedicated spaces on the Campus to address specific needs. In parallel, we negotiated with the main suppliers of the software used to teach in order to ensure that the applications in the context of centralized licensing could be adjusted through the temporary availability of individual licenses. All these measures contributed to the increase of the stakeholders’ readiness for the adoption of the innovation, as well as their satisfaction with the process.

With regard to the general aspects of information security and portability and the guarantee of availability of the systems throughout the entire process, tests were carried out and improvement processes were implemented in order to guarantee the installed capacity:

- Robustness, both of the servers and the database of our b-learning system (Moodle). At the same time, a redundancy system was implemented with three competitive Moodle servers, ensuring the necessary resilience in the main EAD assessment and monitoring tool. Alarm systems were also implemented on this solution;

- All authentications respect a strict process based on centralized and/or federated authentication;

- Review of backup copy policies, promoting the development and implementation of alarm systems and process automation with this regard;

- Ownership and internal control of information. The assessment systems data are proprietary and they are not outsourced, therefore, the HEI has total control over them;

- Review of defence policies and mechanisms against external intrusions from security equipment manufacturers;

- Data Centre requalification by providing it with modern redundancy solutions (systems, energy and air conditioning);

- Implementation of a more effective Disaster Recovery Plan system;

ii) Digital Capacity Building

Within the scope of digital capacity building, more than 100 training sessions were planned and held during the period under analysis, for teachers and students, on the use of the different tools available for distance learning (Moodle, Zoom, Teams, Educast), and on distance learning pedagogical practices. In addition, sessions were created to answer general doubts.

With this regard, we should mention the creation of regulations governing the use and good practices in the different components:

- Application - availability of good practice manuals, design and availability of templates;

- Pedagogical - design and availability of models, adjustment of CUF (Curriculum Unit Files), several guidelines regarding the adjustment of pedagogical practice;

- Administrative - creation of procedures for obtaining attendance lists in synchronous classes, creation of a reservation system;

- Infrastructure - creation of rules for the loan of equipment, creation of procedures for remote work (VPN, profiles, etc.)

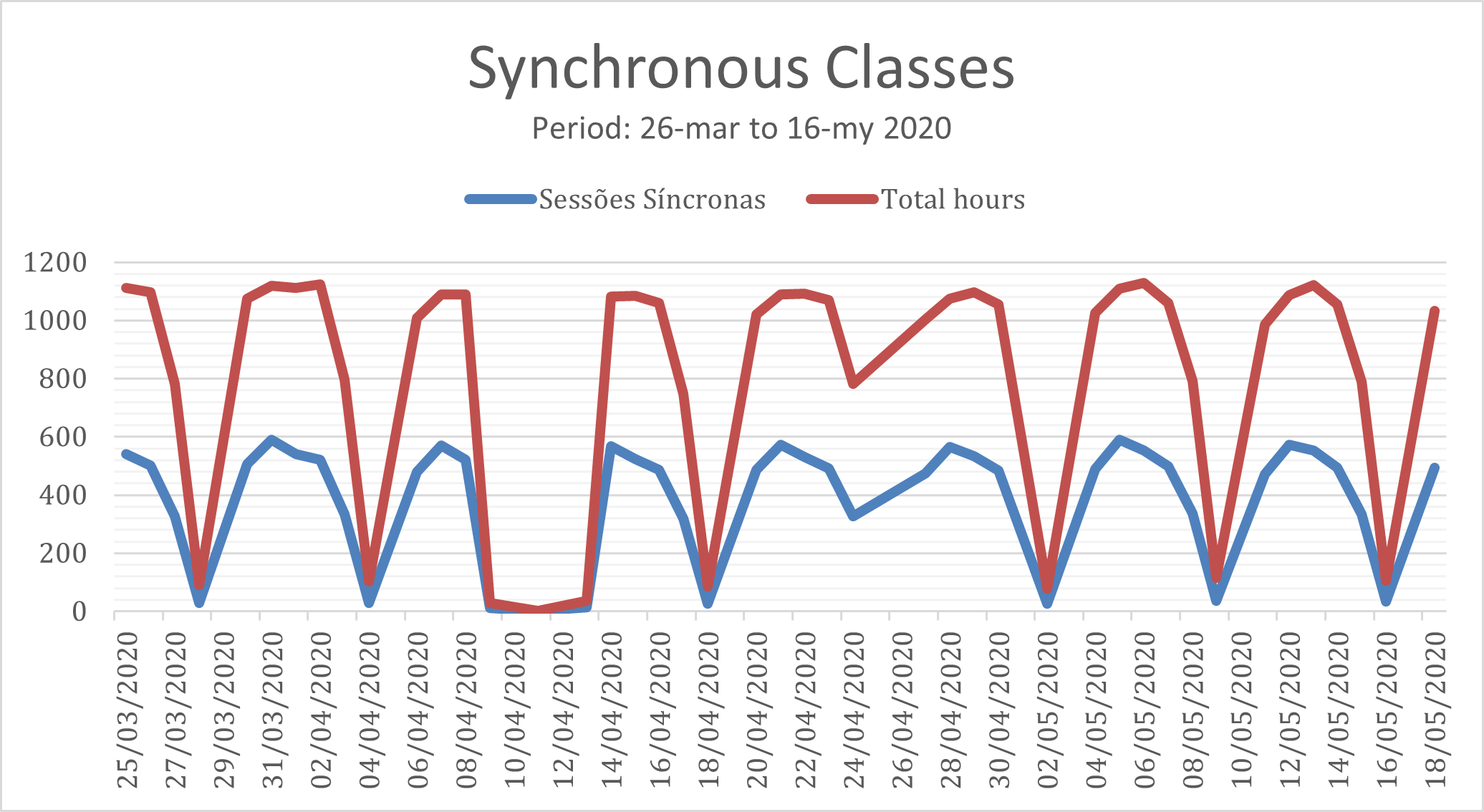

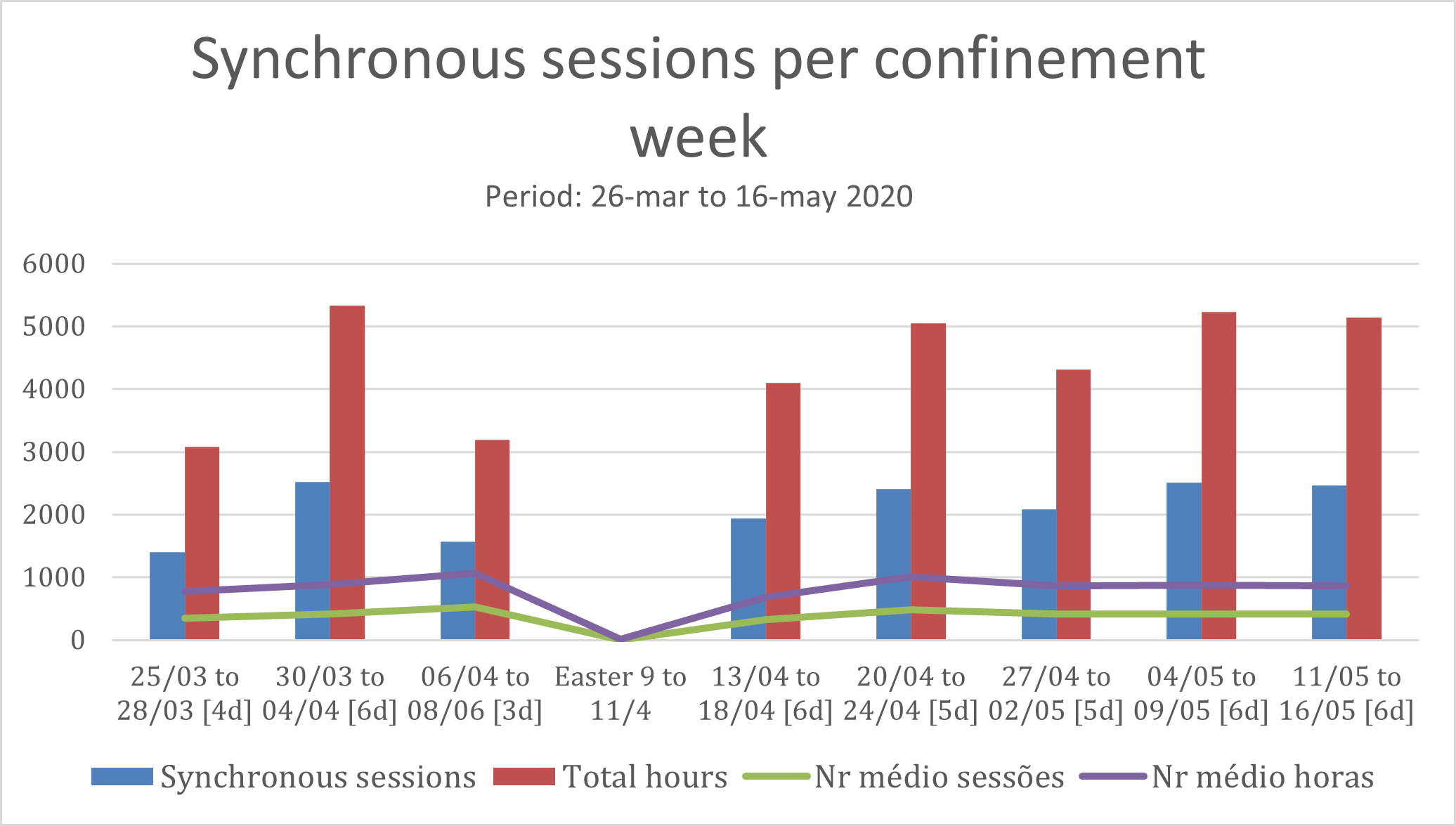

With the implementation of the defined strategy, in the period under analysis - 10 March to 18 May 2020 - we have successfully accomplished 16,961 synchronous sessions, almost entirely through the federated solution Colibri (Zoom) provided by FCCN, in a total of 35,467 hours (an average of 2 hours per session).

By analysing the data, reflected in the graphs above, we can identify an average of approximately 2,500 synchronous sessions per week in a total of 5,000 hours of synchronous contact per week.

In order to guarantee the service quality, surveys were made to students and teachers, before switching to the DL (distance learning) model in order to assess possible constraints to this model of classes, as well as surveys after each session. Specific surveys were also carried out regarding the “Return” to the face-to-face classes. The analysis of the results of these surveys is carried out below.

Following the surveys carried out, as well as through the interaction with the community through the email address created for that purpose (click@ulusofona.pt), where 1,268 mails were received and processed, and measures adopted, such as the loan of equipment , both to students and teachers; the creation of a team exclusively dedicated to the remote assistance, both in training support and skills acquisition, and the installation and configuration of VPN for remote work - 110 VPN remote access accounts were configured; the creation and availability of video conferencing rooms with the necessary resources for distance learning (computer, network, webcam, whiteboard), for teachers or students who required them; or the clarification of several doubts.

The set of services and digital applications integrated by the University in its response to the crisis comprised:

- The Lusófona University’s website, the basis of the communication with the internal and external stakeholders, allowing access to the information and to the entire application set to support the distance learning solution. Built on 10 virtual machines, each with 50 GB storage and 2 GB RAM, in order to guarantee redundancy and load distribution (load balancing, fail safe and stand by - 8 on-line and 2 standby). This system is mounted on a layered structure, with the virtual machines and the middle-tier based on Oracle APEX and the last layer - application servers, supported on Oracle;

- The creation of dedicated support teams that assist and solve all the internal stakeholders’ needs, from procedural and doubt clarification, to technical support, training and even psychological support through an anonymous dedicated line;

- Established as the centralizing platform for all asynchronous teaching, Moodle gives internal stakeholders equal access to information, since all teachers and researchers with contract in the University, as well as, students duly enrolled in the respective cycles of studies, as well as the competent Services of each Organic Unit of the University have access to it via automatic integrations with the ERPs. Any other solution used as a complement to asynchronous training is available through Moodle, including links to synchronous training sessions through Colibri (Zoom) are also available here. Supported on a server with 10 dedicated processors, it currently has 1 Tb storage and 16 Gb RAM. The criticality of this system made us implement redundancy mechanisms with 3 competitive servers.

- For synchronous sessions the decision fell on the Hummingbird (Zoom) provided by FCCN, since it is a reliable, simple tool, with short learning curves and, last but not the least, allowing federated access for the entire academic community;

- Proprietary and dedicated infrastructure. With the exception of Colibri and the complementary systems provided (Office 365, for example), all critical systems are housed in their own data centre, ensuring control over sensitive information (personal data and assessment tools).

5. Teaching/learning dimension - Procedural and Regulatory Adequacy

The teaching/learning dimension obviously played a central role in responding to the crisis because the crisis was triggered precisely by the fact that, with the suspension of face-to-face activities, this relationship was endangered. It is obvious that this was only the first threat posed by this crisis. Much more serious was the fact that, when the teaching/learning relationship was endangered, the fulfilment of the institution's mission and the provision of its value proposal was endangered, thus endangering the very existence of the institution. In response to the crisis, this dimension developed essentially along two axes: the adequacy of pedagogical practices to a digital remote teaching environment, and the production of a significant set of regulations that intended to define the scope of this process in the institutional context.

i) Pedagogical Practices

If with Bologna, tripartite classes (pre-class, class and post-class) came to change the implemented teaching paradigm, with the disruptive change caused by this new reality where teachers and students found themselves obliged to a sudden adaptation to a new teaching paradigm, the need to transform teacher-student relationships into an influencer-follower relationship has become even more obvious.

Thus, and since the distance learning practice requires the adequacy of the teaching model, which is why, after the first phase of digital capacity building training sessions, several training actions on pedagogical practices in distance learning were designed and held in order to assist teachers to streamline the pedagogical content of their curriculum units to the new teaching reality, with themes such as:

- “Organization of pages for collaborative environments”;

- “Motivation using DL (distance learning) methodologies”;

- “Dynamics to support the interaction with students in class;

- “How to create a collaborative learning environment”;

- “The teacher's role in motivating students in the on-line classroom”;

- “Dynamics to support the interaction with students in class while using autonomous work”

This process was once again guaranteed by permanent communication and training actions with teachers and students, promoting their engagement and the monitoring of the whole process. As an example, it should be noted that after each session, teachers and students were contacted by phone and asked to assess the session, identify problems and design solutions together, whether they were of a more technical or pedagogical nature. ii) Procedural adequacy

The list of orders published during the period under review is as follows:

| Order | Description |

|---|---|

| Joint Order No. 8/2020 | Regarding the reorganization of the Academic Calendar - 2nd Semester of the 2019-2020 Academic Year |

| Joint Order No. 09/2020 | Submission of theses, dissertations and other papers in digital format via Moodle. |

| Joint Order No. 10/2020 | Public defence exams for master’s and doctoral degrees by teleconference |

| Joint Order No. 11/2020 | Postponement of submission of final PhD and Master's Degree papers and internships in any cycle of studies. |

| Joint Order No. 12/2020 | Exams specially adjusted and designed to assess the ability of candidates over 23 years old to attend higher education. |

| Joint Order No. 13/2020 | Application Calendar for the 2020/2021 Academic Year. |

| Joint Order No. 16/2020 | Return to face-to-face activity on the Campus of the Lusófona University. |

| Joint Order No. 17/2020 | Renewal of enrolment in the 3rd year of the 3rd Cycle of Studies |

| Joint Order No. 18/2020 - | Approval of the Regulations for the Special Application Regimes of the Lusófona University. |

| Joint Order No. 19/2020 - | Inbound Mobility Students in the 2nd Semester of the 2019/2020 Academic Year. |

| Joint Order No. 20/2020 - | Outbound Mobility Students in the 2nd Semester of the 2019/-2020 Academic Year. |

| Joint Order No. 21/2020 - | Public defence exams for master’s and doctoral degrees during the existence of international travel bans. |

| Joint Order No. 23/2020 - | Exams 2019/2020. |

| Order No. 07/2020 - | Rules regarding changes in assessment due to the application of distance learning determined by COVID-19 contention |

Table 1 - List of orders published during the period under review is as follows:

6. Brand Management

The last of the essential dimensions in Lusófona University's response to the crisis was brand management. To guarantee the success in the relationship with all stakeholders, a brand was created and managed - «Click» - which aggregates the set of services to be provided to the community, such as:

- Click Conteúdos (Click Contents)

Creation of a specific page on the Lusófona University’s website (ulusofona.pt/click) where all students, teachers and employees of the Lusófona Community can find information and ways to access the resources and technologies available for distance learning and collaboration (“Tudo à distância de um CLICK!” “Everything just one CLICK away!”). In this portal, in addition to the availability of the Guidelines for Distance Learning and Assessment, handbooks, videos, tutorials, FAQs and access to the download of collaboration tools are available; - Click Suporte (Click Support)

Together with the Click Portal, support lines were created for the community, through the availability of dedicated telephone lines and an email address (click@ulusofona.pt), with a support service dedicated to the remote configuration of equipment, VPN access and clarification of doubts. We highlight the creation of a completely anonymous dedicated line for psychological support; - Click Reservas (Click Bookings)

In order to tackle the specific needs of teachers and students, the email address reservas.click@ulusofona.pt was created to allow a teacher who did not have his/her own conditions to book a video conference room with the necessary resources for distance learning (computer, network, webcam, whiteboard). This e-mail address is also used to enable a student to book and use a space on the Campus.

In total, and in a relatively short period of time, more than 100 training sessions were held, with a total attendance of around 5,000 people. A good indicator of the interest and engagement of the entire academic community in this process was the fact that, for the first time, and during this period, the volume of traffic the Lusófona University website home page was less than the traffic to the Click portal home page, that is, we had more people visiting Click than the University's homepage.

| Page | Page views |

|---|---|

| /click | 31821 |

| / (home page) | 20231 |

| /system-zoom | 2551 |

| /office365 | 1920 |

| /system-teams | 1618 |

| /click-questions-and-answers | 1298 |

| /resources-e-learning | 1277 |

| /chronicles/for-pos-covid | 921 |

Table 2 - Website pages with the highest traffic volume between 15 and 23 March 2020

By using the management of the Click brand, it was possible to consistently encapsulate all the coordinates considered essential in the pursuit of the guidelines resulting from the strategy developed in the school break period between 10 and 24 March, and continue to communicate in an integrated way throughout the process. At the same time, the fact that there is a single entry point in all essential digital services for access to the innovation was a central aspect of the success of the adoption of the innovation.

After the acute phase of the crisis and already in a recovery stage where some face-to-face activities were developed while maintaining the distance learning in the curriculum units that adapted to this new reality, the same strategy of using a solid, aggregating and involving brand was followed to aggregate the entire process. The “Regresso” brand was thus created and it served as the basis for the definition and planning of the return to face-to-face activities, both for curriculum units whose pedagogical contents are not suitable for distance learning and for those that, if necessary, need a face-to-face complement.

The creation of a single brand aggregating the whole process was a central aspect of the Lusófona University’s response strategy to the crisis. This brand made it possible to facilitate the communication process with the stakeholders in order to guarantee their engagement, create a unitary perception of value and aggregate what would otherwise be dispersed digital services, on a single platform, thus creating, based on already existing technology, an innovation as a way to respond to the crisis.

The creation of a single brand aggregating all the dimensions was one of the most differentiating aspects of the Lusófona University’s response to the crisis.

Up to this point in our paper, we have identified and described the four dimensions that integrated the Lusófona University's response strategy to the crisis caused by the CVID-19 pandemic. We have seen how these four dimensions complemented each other in order to ensure the adoption of the innovation introduced as a response to the crisis - remote teaching using digital teaching and communication platforms - and we have highlighted the central role played by the engagement of the internal stakeholders in this response to the crisis. In the rest of the paper, we will describe in more detail the specific case study, underlining, where relevant, the aspects of the institution's response that seem most relevant to us as points to retain for lessons about the future.

7. Chronicle of a crisis

10 March 2020. 12h. In a major meeting, the Lusófona University’s Rectorate and Board of Directors decided to interrupt the teaching activities on its Campus. An unprecedented decision in the history of the University. At the time of the decision, there were 41 people infected with COVID-19 in Portugal, in a total of 119,019 cases identified worldwide. As of the writing of this paper, there are 7,182,929 cases identified worldwide. In Portugal, the total number of cases on the same date is 34,885. On 10 March, when the decision to close the university was made, it was impossible to predict the evolution of the number of cases and the mortality rate associated with the virus. In all decisions made in times of uncertainty, there is a huge risk and also an enormous exposure to contradictory voices. In making the decision, different opinions, fears and certainties against and in favour of closing were heard and taken into account. The uncertainty about whether we were following an overly alarmist line in contrast to the risk to which we would be submitting the entire community of students, teachers and staff, by not deciding on closing, was felt by the University's decision-making bodies. The decision to close was made. All teaching activities were suspended, at first, until 24 March. Along the same line, the suspension of face-to-face activities at other Higher Education institutions followed, until on 16 March, Prime Minister António Costa decided to close all teaching activities of all levels of education in Portugal.

What was in the week before 10 March a university campus in full activity, on 11 March became an empty campus, without students, teachers, although with some employees who, 16 from March started the teleworking regime for the most part. In this way, a space that is by nature noisy, busy, alive, has become an empty space, without students, without teachers. The modern academia was not only living under the risk of a pandemic, it was also beginning to feel the deprivation of its intimate space, of its reason for existing. Academic campuses are exchange, growth, and challenge spaces. On 16 March 2020, they were deserted spaces.

Given this surprise, the University’s decision-making bodies probably made the only decision they could make: to resume teaching activities that could be resumed by switching them to the distance learning system. On 12 March, it was decided that classes would restart on 25 March. The entire structure of the Lusófona University had 10 days to guarantee the conditions to resume teaching activities.

To get a University with about 12,000 students and more than 1,000 teachers to work with a distance system in such a short time was an enormous challenge. Despite having been combining much of its face-to-face teaching with distance learning systems, such as the cases of Moodle, Colibri, among other services made available by FCT/FCCN for more than a decade and a half, the Lusófona University had never tested the total absence of the face-to-face component in teaching on such a large scale to date. This was the main challenge. How to have 12,000 students and 1,000 teachers developing their academic activities in a 100% distance system in a period of 10 days? How to ensure digital capacity building and training for all players? How to assess the technical conditions of access to on-line teaching? This part of the paper will describe how the process of adapting to the distance learning system took place, an effort made between 10 March and 18 May and which corresponded to the acute period of the crisis.

Phase 1

The first action taken was to assess the conditions for switching to a remote class system with the teaching staff and students. This decision, however, would also have to find an answer for classes that could not be taught on-line, as is the case with practical, laboratory and internship subjects.

At the Lusófona University, several programs are taught for which there is a huge practical component that simply could not switch to the distance learning system. For all the cases identified together with the different Program Boards, the following decisions were made:

- The practical subjects would be taught in the months of May, June and July;

- Where possible, the practical subjects would be transferred to the following semester, in exchange for the theoretical subjects;

- The internships would be temporarily suspended until the conditions for their completion were guaranteed.

All the Boards of the different cycles of studies were asked to list, within 2 days, the subjects that would, from 25 March, work in the distance system using both the video conferencing and asynchronous distance learning systems. The time was short and the University’s Rectorate and Board of Directors knew that the time available for adapting the contents to a remote system was probably insufficient. Two dimensions of risk were assessed: the risk of the University being paralyzed in what is its main mission, and the risk of starting teaching activities in the distance system without having a clear perception of the technical conditions, teachers and students infrastructure and, finally, the pedagogical and methodological conditions of its teaching staff for the forced move to on-line activities. Although training is guaranteed at the beginning of each semester for all teachers on how to use the Moodle and Zoom tools, among others, the perception at the time was that there would certainly be extra training and follow up needs on the part of teachers and students due to this sudden change.

Phase 2

Phase 2 started formally on 16 March with two moments that proved to be decisive for the success of the whole operation. On the one hand, the creation of a unique brand to aggregate all communication with the academic community during this period. The Click - Tudo à distância de um click (“Everything just one CLICK away!) brand was created with the central objective of simplifying the access to information and communication and, at the same time, to be a unique channel through which all requests for support could be centralized.

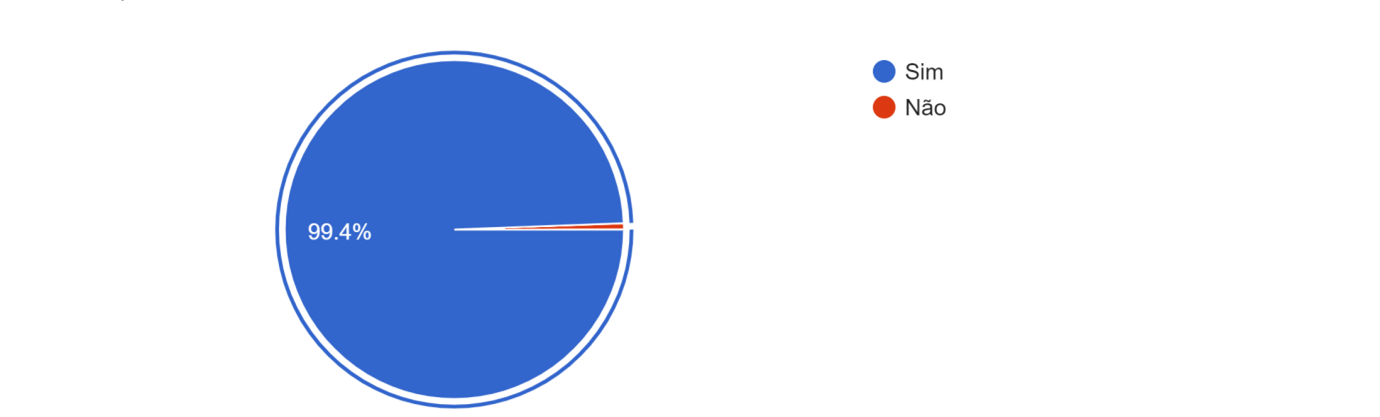

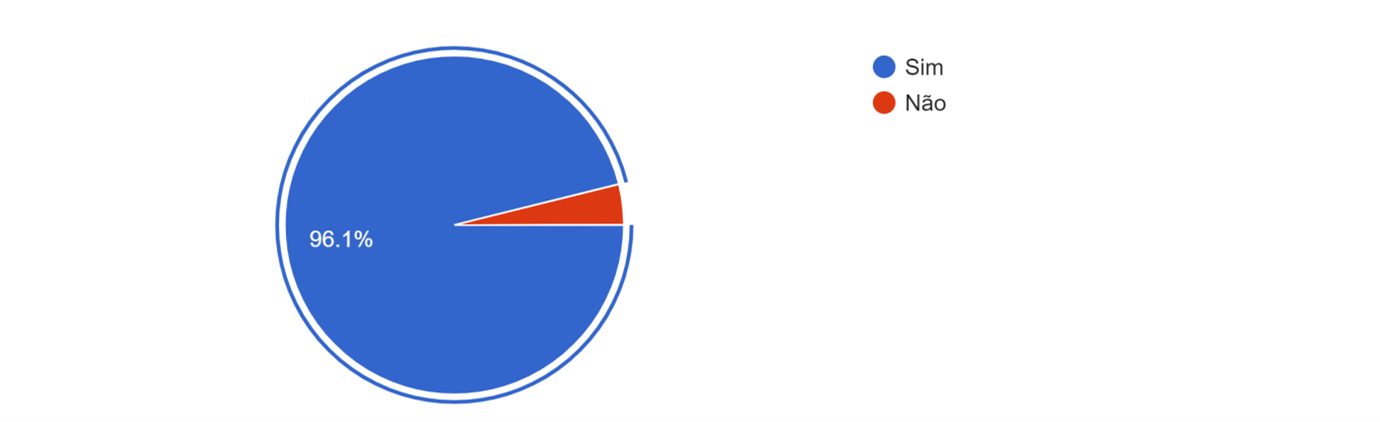

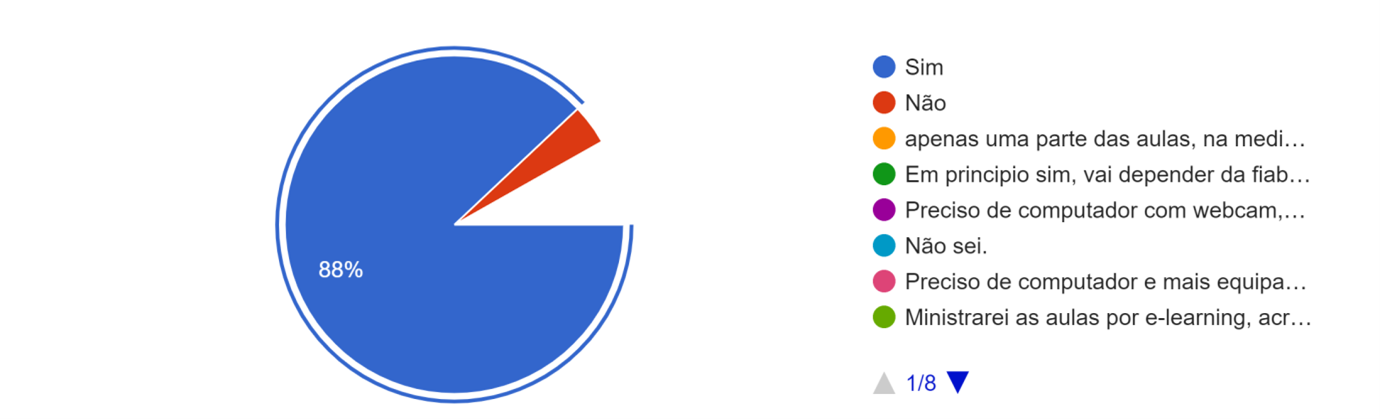

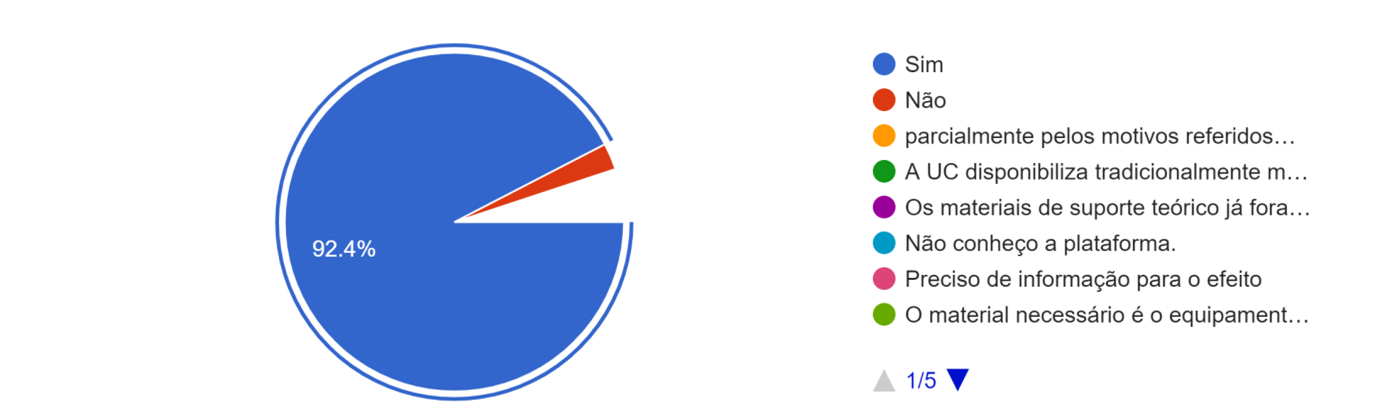

On the other hand, already under the Click brand, the first questionnaire was sent to all teachers in order to assess the technical conditions of the teaching staff for conducting classes via video conference. The questionnaires were sent only to the teachers who would teach their classes on a distance basis. This universe of teachers resulted from the list made by the Boards of the Cycles of Studies that had been requested on 12 March. 676 (n = 676) valid answers were obtained between 16 and 18 March, which represents about 60% of the total teaching staff, corresponding to about 90% of the teachers selected to teach their classes from 25 March. Among other questions that were part of the questionnaire, the most important were:

- Do you have an Internet connection at home?

- Do you have devices with webcam and microphone (laptop, tablet, desktop)?

- Do you consider that you can guarantee your classes through a videoconference system?

- Do you consider that you can guarantee the availability of the materials necessary for classes on the Moodle platform?

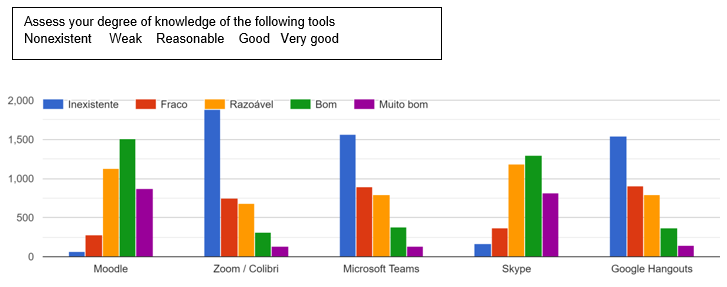

- Assess your knowledge of the following tools (Moodle, Zoom / Colibri, Educast, Microsoft Teams, Skype, Google Hangouts).

The answers to these questions made it possible to draw a picture of the needs and conditions of the teaching staff for the transition to an on-line system. In this context, it was necessary not only to diagnose the pedagogical conditions for on-line teaching, but also to know the technical conditions, the equipment and infrastructure conditions that each teacher had and whether they guaranteed the minimum conditions required to teach on-line classes.

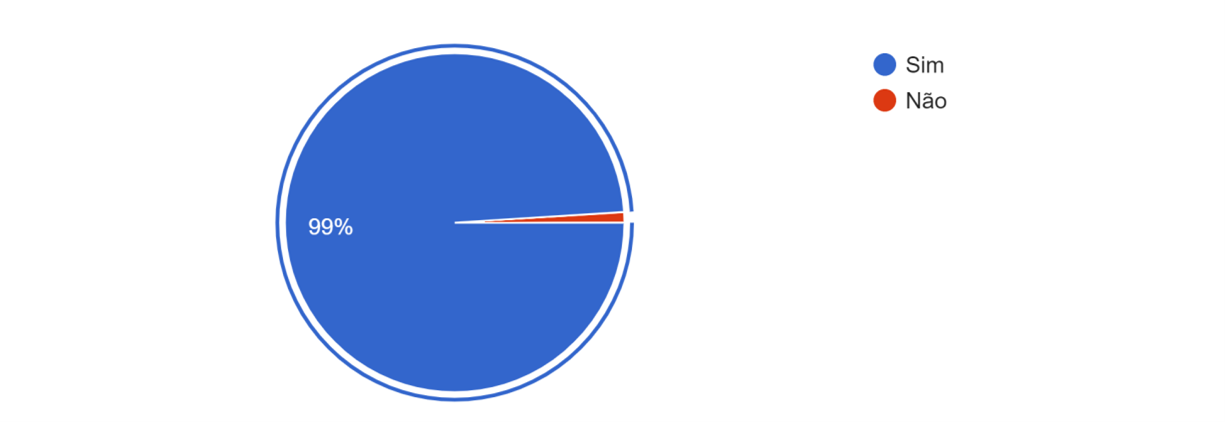

99.4% answered that they had an internet connection at home, which is in line with the figures made available by ANACOM for the 1st quarter of 2020 which indicate that 81.5% of the Portuguese families have an internet connection at home.

The answers related to the remaining questions pointed out that there are objective conditions that made the return to classes on 25 March possible.

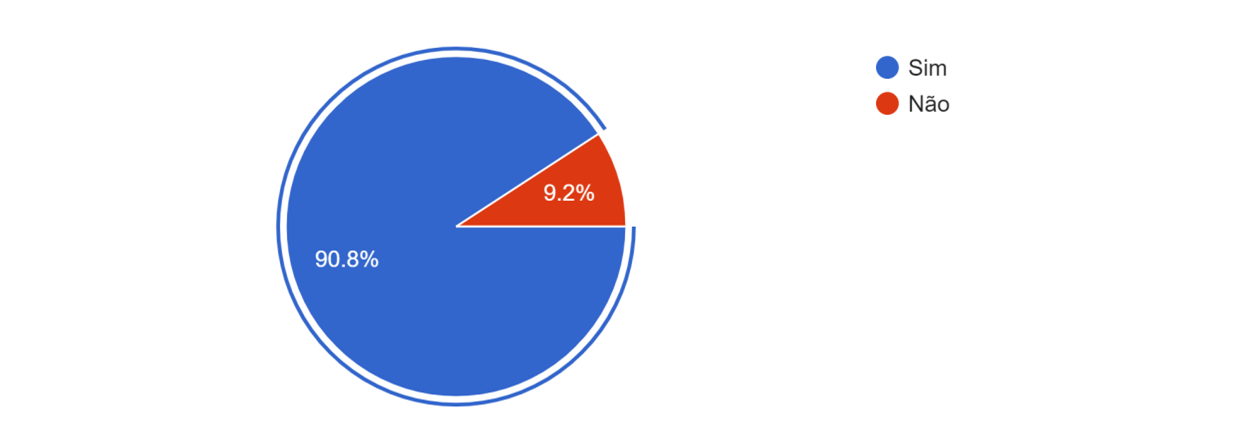

Of the teachers surveyed, 88% answered that they considered having the conditions to conduct classes via video conferencing systems.

An overwhelming percentage of respondents (92.4%) considered they were able to make materials available for classes through Moodle, with a large number (80%) already doing so before the pandemic.

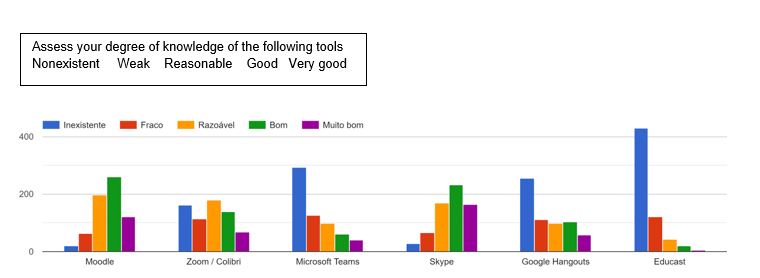

In terms of knowledge about the set of tools made available by the University for distance learning, it was important to understand, in addition to the Moodle system, for which training actions are often carried out with the teaching staff, which systems were available for which there was greater need for training.

The data showed that Moodle, Zoom and Skype are the systems for which there is a greater degree of knowledge, with Moodle, as expected, being the best know by the teaching staff.

In the same period in which the first questionnaire was sent to the teaching staff, and still within phase 2, a similar questionnaire was sent to the students. It was fundamental to understand the conditions for students’ access to on-line classes. If the two parts of the equation did not present conditions for returning to classes on an on-line system, it would be impossible to guarantee a successful return to classes on 25 March. The questionnaire that was sent to the teaching staff was adapted and was sent to students enrolled in the curriculum units chosen for the return on 25 March. The results of the questionnaire to students were similar to those of the questionnaire to the teaching staff. In this way, the conditions for restarting classes in the on-line format were ensured. It was necessary to have a campus in motion again. In this case, it would be motion at a distance, virtual, but it would nevertheless be resuming what is the mission of all HEIs: teaching.

3,891 (n = 3,891) answers to the questionnaire sent to the students were obtained, representing about 35% of active enrolments, and 70% of the universe of students that would have a direct impact by the return to classes in distance format, that is, the students enrolled in the 2nd semester of the 2019/20 academic year in curriculum units that were going to switch to a remote teaching system.

99% of students said they had an internet connection at home. Figures identical to those presented by teachers and above the national figures indicated by ANACOM.

The overwhelming majority (90.8%) have equipment with microphone and webcam, which is a basic requirement for accessing contents provided remotely.

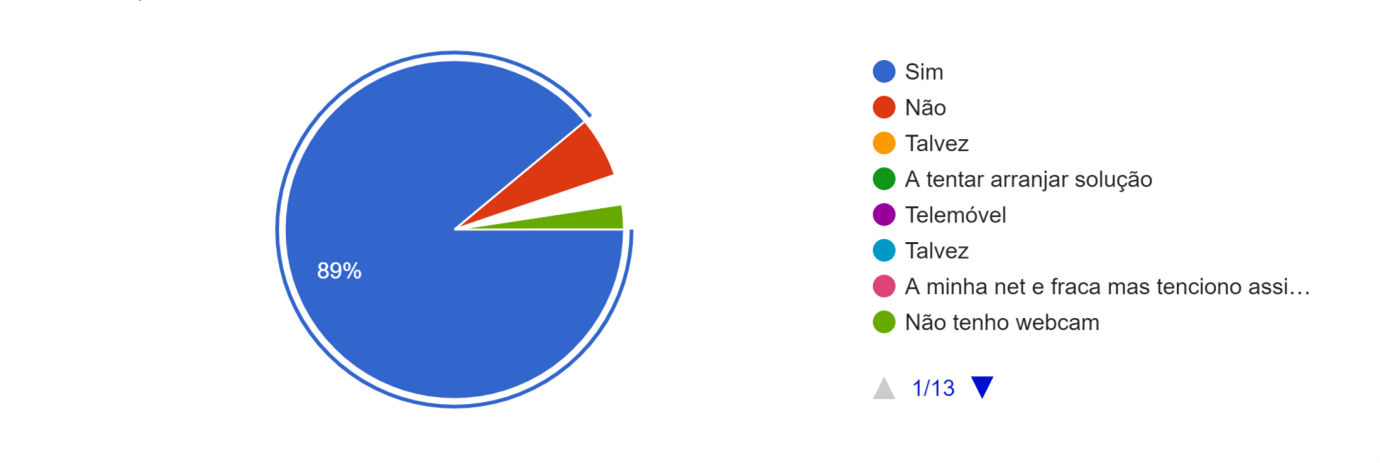

Approximately 89% of the surveyed students considered that they were able to attend classes via video conference. The problems and constraints presented by the remaining 11% of students who indicated that they considered not being able to do so had to be solved. That would be the mission of the Click team members - to find a way to get these students to attend classes.

In terms of knowledge of video conferencing and distance learning systems and tools, Moodle and Skype were the systems that people were more familiar with. The Zoom / Colibri, provided by FCCN, was the system that would be formally adopted for distance classes. This was yet another important decision by the institution: to opt for a managerial logic in the establishment of the technological solution by not allowing users to choose the platform that they were more familiar with, and rather “imposing” a platform which the institution knew it could guarantee better support. If the numbers presented by the teachers about this system already indicated the urgent need for training strengthening, the figures presented by the students made training in the use of Zoom as an imperative factor for the success of our strategy.

In the week between 16 and 20 March 16, and as the results of the questionnaires became known, daily training sessions were scheduled for students and teachers on how to use Moodle, Zoom, Kahoot and Microsoft Teams. The training calendar was updated on the Click portal on a daily basis. Adherence exceeded all our expectations. Several training sessions were held for teachers, some with the presence of more than 150 people and for students with several sessions with more than 200 students in different training sessions for Moodle, Zoom and Microsoft Teams from the perspective of the student user.

The Zoom/ Colibri and Microsoft Teams training sessions for students had two main objectives: (1) help students in accessing on-line sessions and managing audio and video settings and (2) raising awareness to good practices and rules of conduct in on-line sessions. There were raise awareness actions with the students related to the respect for the time and space of the class. They should avoiding attending classes sitting on couch or in bed, and whenever possible, they should find a space where they could write, take notes as if they were in a face-to-face class.

The different sessions followed a training plan previously established for each system. If for Moodle the focus was on strengthening the training in Curriculum unit management, tests and submission of papers and good practices for making links available to students for remote classes, for the Zoom/ Colibri system sessions were prepared covering technical issues relating to settings and scheduling of remote sessions, as well as good practices in managing on-line sessions, rules of conduct for students and class attendance management and recording.

Phase 3

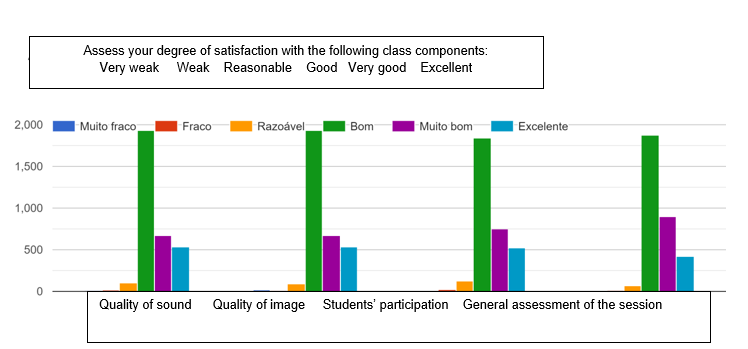

Phase 3 corresponds to the period between 23 March and 8 April, 15 days after the on-line classes started. It is a crucial period in which different actions to monitor and reinforce the training and follow up of teachers and students were carried out. The Lusófona University’s Rectorate and the Board of Directors decided to create a tool to assess the classes that were taking place on-line. At this phase, it was essential to monitor the classes and for that it was decided that the University Call Centre should contact all the teachers who were teaching on-line classes shortly after each class ended by phone. A class map was created with the respective schedules, course, subject and teacher. Shortly after the end of each class, a phone call was made to assess how the class had been based on previously established criteria. 2,475 telephone calls were made on the ten days following 25 March. During these telephone calls, the teacher was asked to assess the class in 4 parameters. The teacher was also asked to point out any difficulties or problems experienced during the class or the need for additional support.

The result of this action showed that the process was evolving in a very positive way, and few problems were identified during the classes. The teachers' assessment of the quality of the classes was generally positive. The training sessions pace was maintained, and they were adjusted to the return and the difficulties reported by the teachers during the assessment process. The problems detected, whether of a technical or pedagogical nature, were referred to the Click portal team for resolution. The follow up of the identified situations was managed centrally through the creation of support tickets. Their resolution management was monitored by the support team on a permanent basis, with contacts made to follow up and check their resolution.

Simultaneously, telephone questionnaires were applied to students with a view to assess the experience of distance classes reported from the students' point of view. The questionnaires were applied during the same period after the start of the face-to-face classes, that is, within 10 working days from 25 March.

There were 1,111 responses from students that globally revealed a very positive assessment of the course of the classes, both at a technical level (sound and video quality) and at a pedagogical level (pedagogical contents, participation of the other classmates). However, the students' doubts about a large range of issues, ranging from questions associated with conducting assessment tests, payment of tuition fees, using video in class, among others, were being followed up, catalogued and answered through a frequently asked questions and answers page available on the Click portal. Two Questions and Answers pages were created. One page dedicated to Teachers and another one dedicated to Students . These pages have been maintained and updated based on the doubts raised by the academic community.

At the same time, the University's Rectorate and Board of Directors published specific orders and Work Orders to deal with the situation associated with Covid-19, establishing new rules and procedures adjusted to the situation experienced. In total, within the scope of Covid-19, 14 Joint Orders were published. Adjustments were made according to the evolution of the situation in Portugal and always in line with the guidelines issued by the government and the Directorate-General of Health. All published documents are available online on the University's website at https://www.ulusofona.pt/noticias/despachos-covid19.

Phase 4

Phase 4 corresponds to the period between 8 April and 18 May. During this period, the schedule of training and monitoring of teachers and students was kept in order to optimize the distance classes’ model. The Lusófona University Digital Academy - Lusófona X was publicly launched. This is a response to the need to enlarge the Lusófona University’s training offer beyond the face-to-face regime. The Covid-19 crisis accelerated this process and on 14 April the first two courses were launched on the Lusófona X platform, which is based on the Open edX platform. The courses offered in this first phase were Drawing for Graphic Diary and Foundations of Programming.

At the same time, the return of some students to the campus for face-to-face classes was being prepared, in particular for practical and laboratory classes that had been suspended. In the second half of April, with the expected end of the state of emergency, the regulatory and guiding preparatory procedures for Return to the Campus began. On 17 April, about 2 weeks before the government lifted the state of emergency and declared the state of calamity, the Office of the Minister for Science, Technology and Higher Education published a Recommendation and clarification to scientific and higher education institutions for the Preparation of plans for the progressive lifting of containment measures motivated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Following this recommendation, the Lusófona University’s return plan was published on 28 April.

For the return, a communication action was planned for students, teachers and staff to raise awareness and disseminate the rules and conditions for returning to the campus - Return to the Campus Plan: Together again... But at a distance. This included the operation rules for the campus, the expected adjustments to the academic calendars and the conditions for teaching some subjects in a face-to-face system.

The schedule for the Return was as follows:

- On 4 May, the opening of some services for organization purposes, only for employees;

- On 11 May, Students, Teachers and Researchers received authorization to go to the Campus and to hold meetings in groups of less than 5 people;

- On 18 May, return to face-to-face activity in practical and laboratory classes in the situations provided for in the return plan.

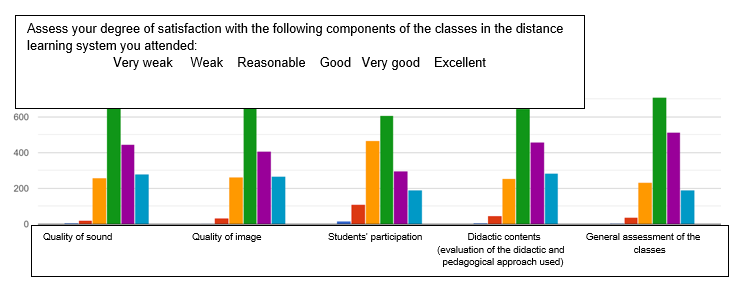

One of the first actions upon Returning was to try to understand what the students' perception would be of a possible return to the campus for face-to-face classes if this were decided. On 21 April, a few days before the publication of the University's return plan, a questionnaire was sent to all students from the Lusófona University enrolled in 2nd semester subjects in the 2019/20 academic year. 5,318 (n = 5,318) answers were obtained within 3 days.

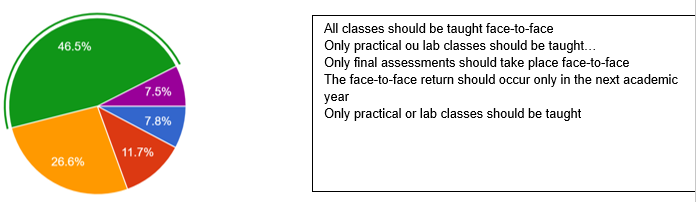

The majority of students who responded to the questionnaire (46.5%) consider that the return should only happen in September, that is, at the beginning of the academic year 2020/21. If we add this percentage to that of those who answered that the return should occur only for practical classes (26.6%), to those who answered that only practical or laboratory classes should be taught face-to-face (11.7%) we obtain a percentage of 84.8% of students who prefer to remain preferably in the distance system, mentioning the need for face-to-face interaction to the minimum possible. The established Return plan reflected and respected, as much as possible, what was the will of the student community. However, we believe that it is important in the context of this paper to reflect on the trend of students’ answers.

As we will analyse in the following graphs, and contrary to what would probably be expected, that is, that there was a strong desire to return to the face-to-face system, the students clearly stated that they were not willing to take risks and, whenever possible, they preferred staying at home, watching and participating in teaching activities in the distance mode.

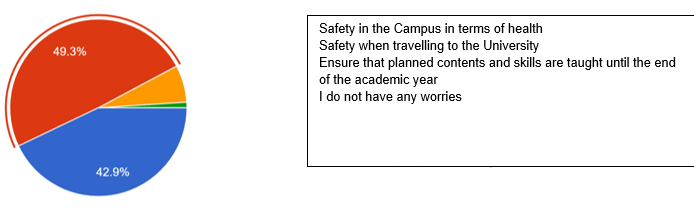

In the opinion of the students, face-to-face return should be limited to the essential. Everything that could be kept on-line should be kept on-line, thus postponing the return to the campus until September. According to the answers obtained, the reasons that support this desire were not only related to the conditions of the return to the Campus (42.9%), but also to the conditions external to the Campus, namely in what concerns safe travel to the University (49.3%). Only 1% of students reported not having any worries about returning.

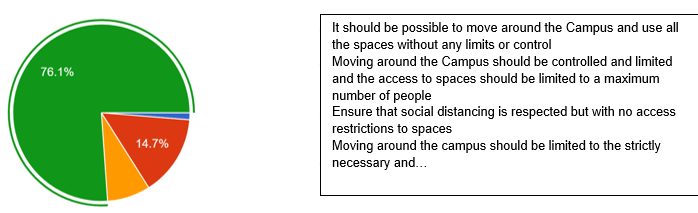

When asked how the circulation on the Campus should be done when returning, 76.1% pointed out that the circulation on the campus should be limited to what is strictly necessary and for a short period of time (practical classes or assessments if they were to take place face-to-face).

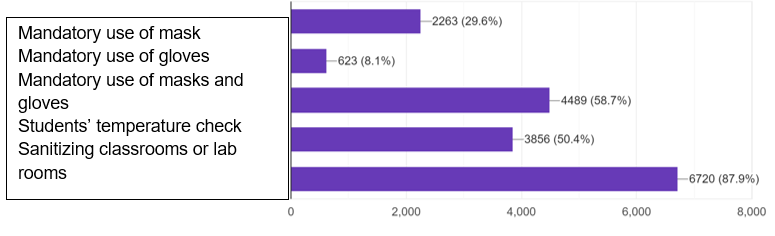

Finally, with regard to the public health measures that should be put in place when returning to the Campus, a large number of students consider that the use of a mask and gloves should be mandatory (58.7%), as well as checking the temperature before entering the Campus (50.4%). Lastly, the vast majority (87.9%) considered that sanitizing classrooms and lab rooms after each class is one of the most important measures when returning to face-to-face classes.

After the 18th, some of the practical and laboratory classes were resumed. There was some expectation and anxiety about the return of students to the Campus. The Campus had been sanitized, the services were equipped with acrylic panels and procedures to ensure social distancing had been adopted. Some of these services started to operate exclusively based on scheduled days and times. The maps with the calendars of classes in progress and relevant information on the program, subject, teacher and list of students were distributed to the competent services so that the hygiene protocol could take place during the half-hour break defined between each class.

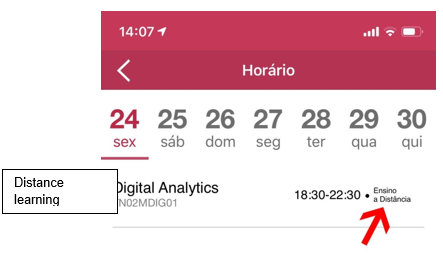

The timetable information was updated on the mobile app even before 18 May, so that all students knew exactly in which system their classes would take place and it would be easier for students with practical classes to identify those classes in the face-to-face system. The Lusófona Mobile mobile app, available for iOS and Android, in the period under analysis in this paper, was accessed by 13,535 users. These 13,535 users generated 713,525 screen views.

8. Conclusions - what are the lessons and challenges for the future of higher education?

Throughout this paper we described the Lusófona University’s response process to the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. We saw that this crisis resulted from the interruption of face-to-face activities at the institution and we classified this crisis as a “total” crisis, which in its acute phase, challenged the existence of the institution itself. We saw how in order to respond to the crisis, the institution developed a strategy based on the multidimensional adoption of an innovation - remote education mediated by digital teaching and communication platforms, having, for that purpose, followed a four-stage process that corresponded to: a) Identification and categorization of the phenomenon that triggered the crisis; b) Identification and characterization of the stakeholders to be involved in the resolution; c) Selection and preparation of the crisis response strategy; and, d) Activation of the response system. In order to activate this response system, the institution integrated multiple features across four dimensions: the institutional, the technological, the teaching/learning and the brand management dimensions.

Given the above, we can conclude that the successful response to the crisis, assessed based on the stakeholders’ degree of satisfaction, was essentially due to the engagement of all stakeholders and the effective communication established with them through the integrated management of the Click brand, together with a good installed capacity in terms of physical and technological infrastructure, permanent communication with the stakeholders and permanent support at various levels, including training, as well as permanent process monitoring and assessment.

The HEIs will face many challenges in the future. This case study shows that the introduction of “innovative teaching and learning practices adapted to a mixed and differentiated education system at all levels of higher education” as advocated by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education through the “Skills 4 post-Covid - Skills for the future” initiative (MCTES, 2020) will need the definition of new models, which, as we mentioned, go far beyond the adaptation of technological platforms or teaching and learning processes, and can only be successful with appropriate strategies for the stakeholders engagement and for communication and management of the adoption process of the innovations concerned. The coronavirus pandemic promoted the centrality of digitalization in the organizations’ processes and accelerated the maturity of digital technology (Sneader & Sternfels, 2020). In this context and in order to guarantee, both the innovative teaching-learning practices and the effective inclusion of their stakeholders, there are several questions that IES will have to answer in the future with this regard: “What models to implement and how to adapt the organizational structure to them? How to ensure inclusion? How to ensure the development of appropriate and positive value proposals for all the stakeholders? What is the technological base to adopt? How not to turn technology into a guru that is going to save everything (Morozov, 2013)?”

Today, as we are still living in a crisis recovery context and we do not know if this crisis will occur again in the short term, these are questions that we all must ask ourselves and for which the answers are not clear. However, there is an obvious conclusion that we can draw from this case study: besides all the differentiating factors that have contributed to the success of the process - the integrated brand management; the stakeholders’ engagement through the support and training and the adequacy of the technological infrastructure - there is certainly a positive factor that has definitely contributed to the success that we sought to illustrate in this case study: it was the isolation caused by the pandemic that ensured total readiness for the adoption of innovation by the stakeholders. That is why, more than any other factor, the crucial question for the future is whether and how we want to do it, to motivate people to adopt more digital technologies to support their teaching and learning processes.